We are not the first

There is an old archaeological trope that absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.

This trope is important to remember when dealing with not just recent archaeology, but also the dark depths of prehistory, when we have scant evidence of anything – the odd jawbone or tooth, the remnants of stone tools, but nothing, really, organic – not much evidence for textiles or woodworking, and I mean WAY back, 30,000 years ago plus. But these things must have existed.

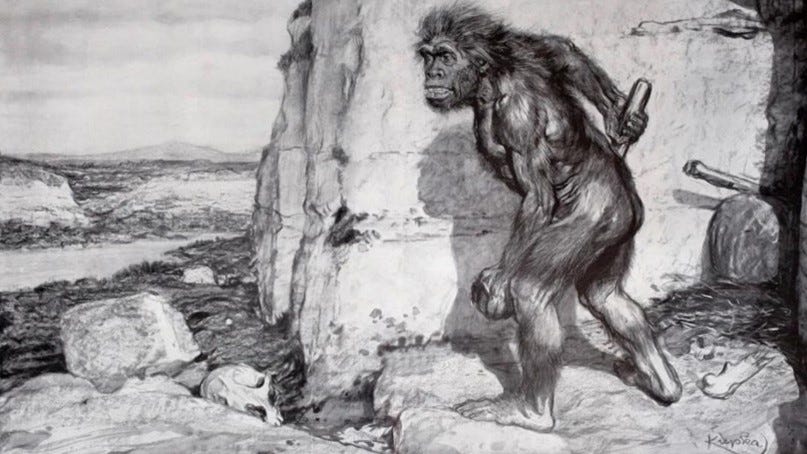

And yet we allow this lack of evidence to colour our picture of the past, so it often looks more like the opening shot of 2001, with monkeys jumping about, tossing bones in the air, like this reconstruction of Neanderthal Man from last century

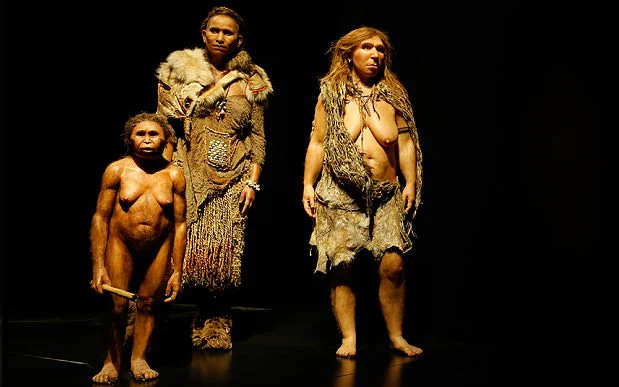

and less like this, below, a more recent reconstruction of a Neanderthal – though it is the former image that dominates people’s ideas of the past.

But we are not just dealing with absence of evidence, here – of clothes, wooden houses, carvings that have vanished - for this presumes what such lost evidence is likely to be. What if the majority of their cultural creations were simply un-preservable, and therefore not just overlooked by modern archaeology, but unimagined? It might have been in the form that leaves no material traces, such as a story, a song or an idea Yet we narrow mindedly expect to find relics of our own technological advancement in the past – and failing to find them, bandy about the words ‘uncivilised’ or ‘primitive.’

What if past civilizations were so utterly different from our own that we simply don’t see the traces of advanced thinking or culture, or just overlook them?

Bear with me.

Not long ago I watched a video on Youtube of an old tv show about up and coming technology. It was marvelling at the compact disk

It explained how a CD worked and stored so much more information than a vinyl record – and at the end, the presenter, with a wry smile on her face, mused that one day we might be able to get ‘Beethoven’s Ninth on a silicon chip.’

Fast forward 42 years, and this prophecy has become reality; indeed, it seems laughably conservative. Take my phone’s SD card as an example. It is ostensibly a bit of gold-coloured foil in a plastic or card rectangle. It’s a tiny sheet of metal, yet it has thousands of images and videos stored on it – it also has room for all of Beethoven’s symphonies, and also all of Wagner’s Ring cycle. Yet it’s a tiny gold square, and unless you have the technology to decode it, a blank SD card looks exactly like a full one. It’s a plain, shiny, flat metal tile. Give it to an archaeologist and ask him to tell you what’s on it. There’s no way he can know. Indeed, the golden mask of Tutankhamun might have encoded on its surface the record of a million civilizations, only we can’t read it.

Do I believe that? No – but it’s possible. What I’m saying is that it is easy to overlook amazing advances, even technological material advances, let alone mental advances that would leave zero trace.

The trouble is our vision of prehistory is mostly empty space, and we fill in the gaps with more of the same, or with what we expect to see. As I said above, Neanderthal man used to be painted as little more than an ape. Today we have evidence Neanderthals produced bones flutes, such as the 50-60,000 year old example found at Divje Babe cave near Cerkno in northwestern Slovenia, made from a bear’s femur.

Now, we can’t have found the only one, the chances of that are laughably slim. So there must have been more. Many versions before and many after. Maybe some in wood rather than bone. And if there was music there was songs. Songs, storytelling and sagas - orchestras. Suddenly the ‘little more than ape’ has become a musician. And this is from one stray find that some still choose to think was for imitating bird-calls (which you can do with fingers and a blade of grass – you don’t need a multi-holed drilled bone)… I prefer to half-hear the haunting melody of a vanished race; a swansong, literally (some of the earliest human flutes were of birds wing bones), an early version of Beowulf, perhaps, whose tale is a version of an older story of the ‘bear cub hero’… just a whimsical idea, I know – but bear heroes no doubt proliferated in Neanderthal and Early Human tales – of which Arthur and Beowulf and but the latest examples (and on which I will write later, but not today) – fitting if they were played on the leg of a bear.

Now imagine this flute playing Neanderthal looking less- like something from out of Planet of the Apes, but as a bearded, squat, powerful individual, in coloured textile clothing. Imagine him, say, like Gimli in Tolkien’s imaginarium.

And now imagine him inhabiting a world with men and hobbits (yes, Homo Floresiensis),

(Models, from left, representing a Homo floresiensis, a Homo Sapiens and a Neanderthal CREDIT: AFP)

And interacting with these Neanderthal Gimlis and also with our ancestors, were other hominids such as the recently discovered Denisovans, whoever they were – and you begin to realise there’s a whole untold tale here, a whole series of lost sagas worthy of Tolkien telling of their lives and interactions - and this is just the species we have evidence for thus far. And we know not a single thing, not a single name, or legend or song of these lost histories; loves which were declared as eternal as Romeo and Juliet have faded, and also the hymns of choirs sang under ancient skies lauding god-kings who like Ozymandias have faded into dust. The wars and alliances between men and Neanderthals; family ties, marriages, alliances, feuds, murder, revenge and forgiveness. And yet in the thousands upon thousands of years that passed in prehistory, surely this all happened, again and again. It can’t have been thousands upon thousands of years of hitting rocks and grunting.

This loss is almost impossible to envisage. Imagine if all we knew of English history was the names of ‘England’ and ‘King Harold’ - no context, nothing. That’s an appalling thought. Now remove both these facts, England and Harold, and that’s how much we know of our pre-civilization ancestors. Zilch. Yes, we know they used certain types of axes, hunted bison, that kind of thing, but nothing personal. That’s like saying the people who lived in the island north of France ate roast beef.

Such a lack of evidence isn’t surprising, though – changes of political landscapes and languages can erase cultures in the blink of an eye.

The scops, the storytellers, of Anglo-Saxon England probably had a song, a saga for every night of the year, for many years, and yet but a single epic, that of Beowulf, remains. All these early sagas were lost almost overnight when the Normans conquered and brought a new language and a new culture with them. In that case it was cultural pressure, rather than time, that erased the memory. You could tell stories of Arthur or Roland in a Norman court, but you can shove your Germanic Ingeld and Wada where the sun don’t shine. Both time and change have erased the tales of the Neanderthals and the early humans. Unless you think that the Dwarves and trolls of Germanic myth are a memory of such folk (again, a subject I’ll return to at a later date).

The lost sagas of prehistory are irrecoverable – likewise the minds that created them. No amount of archaeological analysis can show us inside the brains of our forebears. And yet we do them such a disservice when we fail to give them the possibility of growth and agency, of being able to think as we do, and perhaps to be able to think differently, perhaps better.

We do them this disservice when we limit their development to mirror that of our own, clumsy, mechanical world.

Shakespeare lived in a world without cars or phones, yet he had a whole civilization in his head. Dig up his skull (if you dare) and, like the SD card, you’ll see not a jot of evidence for genius. No glimpses of Hamlet or Othello in the hollow cranium. Genius doesn’t show up on a skull.

What prehistoric Beethoven may have played on that bone flute? We just wouldn’t know.

Instead of fur-clad apes, imagine for a moment a culture akin to, say, the later Polynesians, great ocean sailors, with a strong identifiable culture, highly decorated personally, rich in artistic skill, not bland and drab; imagine for thousands of years such a culture growing rich off the abundant sea-life of tropical coasts; they learn from the stars how to navigate; they sing about heroes who travel the seas, meet strange creatures, dwarfs and giants; they engineer wood to make their boats better, and solve problems, learning more of maths and the motion of the stars; is it unthinkable they might have had a Beethoven or a Shakespeare of sorts among them? Or a Brunel? And such a civilization could have risen and fallen, risen and fallen, many, many times. Look at the way in three or four generations we have gone from cart and horse to SpaceX. That kind of growth seems currently exponential. It may have happened before, but with different technologies, different abilities.

And that may even have developed in ways we can’t imagine. I mean in regard to the development of consciousness. Look how the Eastern world developed yoga and meditation – pushing the boundaries of physical and mental abilities that far outranks that of the West. If the world is, at base, as many now believe, consciousness, then this offers a way for expansion and development that we materialistic moderns so far eschew. Imagine if these lost civilizations developed internally – creating civilizations of the mind, cities of dreams; exploring realms beyond what we think is possible or real. Interacting with forms of consciousness as diverse and real as anything we meet in our material world.

I can feel some of your skin pricking and eyebrows raising. But just imagine.

What if some branch of the hominid family tree developed in a way outside of our perception, beyond our reason?

We laugh at this because we believe we’re the most clever and advanced society ever. We don’t see that every other culture, ever, and many today, see the world in the way I described above, spiritual with the possibility of interacting with other forms or states of consciousness. Even if you don’t believe in other consciousnesses, at least foster the possibility that a prehistoric Da Vinci might, like Nikolai Tesla, be able to explore his own mind so completely as to be able to build within it amazing art and inventions, like a savant, able to calculate prime numbers in an instant – imagine such a mind solving an engineering problem in his head in a moment. Mozart used to say tunes appeared fully formed in his mind; this suggests a wider state of consciousness than we currently credit, the kind of consciousness that Iain MacGilchrist speaks of. That, allowed to develop, untrammelled by the modern Western mindset, might be able to create things we can’t even begin to imagine. They might be able to intuit how to build a pyramid, in a way we can’t even fathom.

Perhaps to them such genius was a gift from, as the name suggests, the genii, the indwelling spirit, or daimon. One could argue whether such daimones are their own entity, or an aspect of the thinker, but this is another modern and wholly unproductive argument. Jung insisted such entities were psychological archetypes. Yet he reports being reprimanded by one such entity, a figure called Philemon, who told him his thoughts were no more his than the animals in a forest were his.

Perhaps such gifts, then, these inspirations and ideas, were, or were perceived to be, from beyond. Gifts from the gods, or the ancestors, or some spirit of place. If that turned up in a myth we’d laugh at the naivety as moderns; yet this is unacceptable. Let us not dismiss the fact out of hand. Perhaps consciousnesses greater than our own reach out and offer wisdom. Most pre-modern societies would say this was true. In a way there’s comfort in this. Modern UFO experiencers often receive messages for us to mend our ways, and it would be nice if some greater aspect of consciousness than we seem to possess, whether or not it is ultimately ours, might be wanting to guide us through our mistakes towards a better way.

Societies all around the world still live this way, and we modern Western folk often jealously try to ape this –jetting off to the Amazon to take Ayahuasca, in the realisation that we’ve lost touch with something sacred.

If a consciousness-expanded civilization had once existed -and there is no reason why it couldn’t have, many times – what traces would it leave? None. Or very little.

Pick up one of their skulls, Mr Archaeologist, and tell me what they thought. It’s as impossible as picking up my SD card and telling me what music is on it.

This skull might be that of a prehistoric Steve Jobs or Marie Curie, a Socrates, Alan Turing or Maria Callas, whose sheer imagination might make yours appear as puny as a newborn child in comparison. They may have possessed a photographic memory, to be able to repeat every word ever said to them, to relay their family tree going back one hundred generations. And they may have been able to look at a piece of gold foil and heard in their minds ear, the complete works of Beethoven, or to gaze at the heavens and turn back the precessional clock in their minds and see an older sky, or a future one.

Jeffrey Kripal has suggested we begin to add modern ideas concerning consciousness and anomalous states into our Western understanding, and to rechristen the humanities the ‘superhumanities’ – to recognise that we are a superhuman species. Author Graham Hancock’s work also opens us to the possibility that we are a species with amnesia. We have forgotten the grand opera that was prehistory.

But we fail to see it. We see a broken bone flute and we suggest it was used as a hunting lure to catch birds. It’s possible, but to me that bird-catcher is at least as amazing as Mozart’s Papageno, multicoloured, comic, capable of laughter and love.

Such a view of prehistory I have suggested above is not only more interesting, but also more optimistic, for it suggests there might be other ways of thinking that we have eschewed and which might yet be employed to save us from our mechanical, destructive ways. Perhaps we are still yet able to build pyramids in our minds; and to travel beyond the stars, not in some primitive rocket pushed forward by expanding gasses, but through expanding the mind, the consciousness that lies at the base of everything.

And not only do I think it likely we can do this, I think it likely that others have already done so. If we did manage it, I do not think we would be the first.

Love this, very thought provoking. I have often thought about this when exploring the stone tape theory or acoustic levitation. Who knows what the ancients were able to achieve, also think a lot about the pyramids around the world being energy harnessing devices rather than tombs......who knows. I'd give anything to be able to.go back and just see, I seriously think we were far more advanced at one point in history but we somehow lost it all. 🤔🤔🤔🤔

Yes! Thank you, John. I think about this a lot when I'm visiting the old stones or out in nature. What could be communicated to me or remembered if I can just expand my mind and senses enough to perceive it?